Anodizing, as a widely used metal surface treatment process, can be defined as a technique that strengthens and protects metal surfaces by creating a controlled oxide layer. But there is much more to this process in terms of technical knowledge and selection factors.

This guide will explain in detail how each anodizing type functions, what makes them unique, and how to balance cost, wear resistance, and appearance influence so you can make the right choice for your project.

How Anodizing Processes Differ

While all anodizing transforms metal surfaces through controlled electrochemical oxidation, the resulting oxide layers can vary dramatically. Understanding these variables is key to selecting between Type I (Chromic Acid), Type II (Sulfuric Acid), and Type III (Hardcoat) anodizing.

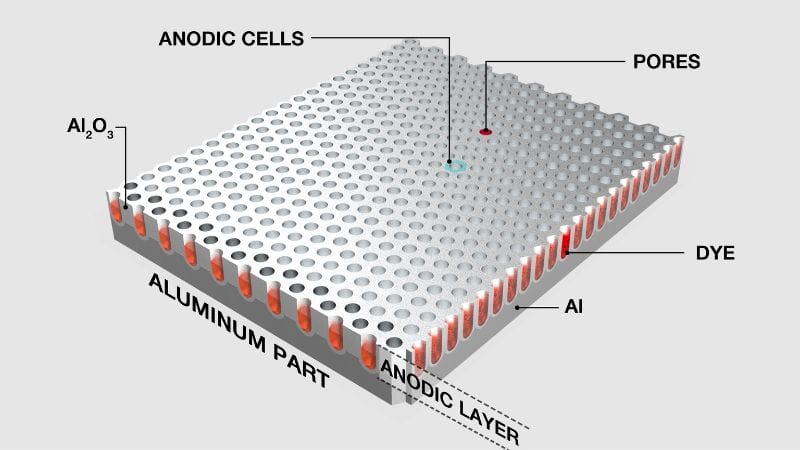

The essential formula is straightforward: the workpiece, usually made with a limited range of metals including aluminum, zinc, magnesium, and titanium, is immersed in an acidic electrolyte, a direct electric current is passed through it, and an integral protective layer grows on the said piece. However, there are four key differentiating variables:

- Electrolyte Chemistry: The type of acid used is the primary classifier. Chromic, sulfuric, and phosphoric acids each interact with metal differently.

- Temperature: Perhaps the most critical operational factor. Lower bath temperatures (~0-10°C / 32-50°F) drastically slow the dissolution of the oxide as it forms, resulting in the denser, harder, and thicker coatings characteristic. Standard decorative anodizing occurs at higher, near-ambient temperatures.

- Current Density/Voltage: Higher electrical current forces a more aggressive oxidation reaction, promoting faster growth and influencing the microstructure of the oxide layer.

- Process Time: Duration in the bath directly correlates with coating thickness, within the limits set by the other parameters.

Type I Anodizing: Chromic Acid Anodizing

Type I anodizing, also known as chromic acid anodizing, uses chromic acid (H₂CrO₄) as the electrolyte. The oxide film formed in such a solution is low-porous and very thin—typically 0.00002 to 0.0001 inches (0.5 to 2.5 microns). This layer bonds tightly to the surface, providing corrosion resistance without noticeably changing dimensions.

Because the chromic acid bath is less aggressive than the sulfuric acid used in Type II anodizing, it minimizes attack on the base and preserves the surface finish. It often serves as a primer base for paints and adhesives due to the excellent adhesion properties of the resulting oxide layer.

Benefits and Limitations

The protective oxide layer from Type I anodizing is thin and smooth, giving the parts a durable but lightweight coating. It provides critical corrosion protection and maintains fine detail on precision surfaces.

Typical coating thicknesses range from 0.00005 to 0.0001 inches, which makes dimension changes negligible. However, it offers less abrasion resistance compared to thicker sulfuric or hard anodized finishes.

Because chromic acid contains hexavalent chromium, the process involves environmental and health controls that restrict its use in some facilities.

Typical Applications

Type I anodizing is primarily specified for aerospace, military, and precision industrial applications where preserving exact dimensions, providing a paint or adhesive primer, and preventing corrosion in weight-sensitive components are critical.

- Aerospace: Used on structural assemblies, control surfaces, flight-critical components, and fasteners where minimal dimensional change and corrosion resistance are mandatory.

- Military/Defense: Applied to precision housings, connectors, and field equipment that require reliable protection and often serve as a substrate for further coating.

- Industrial/Automotive: Employed as a thin protective coating and an excellent bonding or paint base for components where adhesion and corrosion prevention beneath the coating are priorities.

Type II Anodizing: Sulfuric Acid Anodizing

This process generally adopts the same basic principles as other anodizing processes, but the electrolyte solution is substituted by sulfuric acid diluted in deionized water, with temperatures held between 65–75°F (18–24°C).

Coating thickness usually measures between 0.0001–0.001 inch, with thicker layers offering greater corrosion and wear protection.

After anodizing, parts are rinsed thoroughly to remove acid residues, and the pores in the oxide layer can be sealed in hot water or nickel acetate solutions. This sealing step solidifies corrosion resistance and prepares the surface for subsequent color anodizing if desired.

Prominent Performance and Features

Industrial and Consumer Uses

Type II anodizing is the most common process, selected for applications that require a strong balance of corrosion resistance, enhanced surface durability, electrical insulation, and aesthetic versatility for coloring at a cost-effective rate.

- Aerospace & Automotive: Protects structural fittings, assemblies, and decorative trim pieces exposed to atmospheric or mild chemical conditions.

- Architecture: Used for building panels and fixtures where consistent color and weatherability are important.

- Consumer Goods: Found on products like cookware, camera housings, electronic casings, and marine fittings that benefit from improved wear resistance and visual appeal.

- Electronics: Provides electrical insulation and surface protection for components like heat sinks and housings where preventing short circuits is key.

Type III Anodizing: Hardcoat Anodizing

Type III anodizing is also known as hardcoat anodizing. It is characterized by a sulfuric acid electrolyte, low bath temperatures (often 32–50°F or 0–10°C), and current densities around 20–36 amps per square foot.

The thick oxide layer typically measures 0.001 to 0.004 inches. Roughly half of this thickness grows into the base materials and half outward.

This stable low temperature controls the oxide growth rate and reduces burning, which leads to more uniform coatings. Voltage and current density determine final hardness and color, which can range from dark gray to black depending on alloy composition and coating thickness.

Advantages of Hard Coating: Wear Resistance and Durability

Hard anodizing significantly improves wear resistance. The oxide layer can reach 60–70 HRC, making it harder than most steels. This improvement reduces surface damage from sliding, friction, or contact with abrasive materials.

Unlike thin decorative anodizing (Type II), Type III provides long-term performance in demanding conditions such as high pressure or vibration. It also acts as an electrical insulator and can tolerate elevated temperatures without losing strength.

This combination of properties makes hardcoat anodizing valuable for industrial applications where extended service life matters. It limits metal-to-metal wear, reduces maintenance intervals, and preserves dimensional accuracy. The coating’s pore structure can also hold lubricants or sealants to further boost friction resistance and corrosion control.

Critical Use Cases

Type III hardcoat anodizing is specified for components subjected to extreme wear, friction, high pressure, or harsh environments, where maximizing surface hardness, durability, and service life is the primary objective.

- Aerospace & Defense: Protects high-wear components such as engine parts, landing gear, actuators, and firearm receivers.

- Automotive & Marine: Used on pistons, valves, suspension components, and other parts exposed to significant heat, friction, and corrosive elements.

- Industrial Machinery: Applied to gears, hydraulic components, molds, and other equipment where part failure would be costly and extended maintenance intervals are needed.

- Sporting Goods & Electronics: Provides a hard, protective surface for bicycle components, and offers insulation and durability for electronic housings and connectors.

Other Specialized Anodizing Methods

Beyond the main types, several specialized anodizing methods serve specific technical and aesthetic purposes. These processes modify the oxide layer’s thickness, structure, or appearance to meet certain design or performance needs.

Sealing and Post-Treatment Options

Hot and Cold Sealing Methods

Sealing closes the microscopic pores formed during the anodizing bath. The two most common approaches are hot sealing and cold sealing. Hot sealing uses deionized water or nickel acetate at around 95–100°C. The heat hydrates the aluminum oxide to form boehmite, which swells and fills the pores. This method provides excellent corrosion resistance but can slightly dull bright colors.

Cold sealing operates at lower temperatures (25–35°C) using fluorine-based nickel salts or other chemical agents. It saves energy and shortens cycle time, which can lower production costs. Cold-sealed coatings tend to retain color brightness better but may offer slightly less durability against harsh environments.

When choosing a sealing method, factors such as part geometry, desired finish, and exposure conditions help determine which process gives the best long-term results.

Dyeing and Coloring Techniques

Before sealing, anodized parts can be dyed to achieve a wide range of colors. Color anodizing works because the oxide layer is porous and absorbs dyes easily. Common dye types include organic dyes for vivid colors and inorganic metallic salts for fade-resistant hues.

Dyeing occurs right after the anodizing bath, when the surface is still open and receptive. Once color application is complete, parts are sealed to trap the pigments within the oxide pores. This step improves UV stability and wear resistance.

Some applications use electrolytic coloring, where metal salts are electrically deposited into the pores to produce bronze, gray, or black finishes. Integral coloring, a more advanced method, forms color and oxide simultaneously during anodizing. Each technique balances aesthetics, cost, and environmental stability depending on the part’s use.

How to Choose From Types of Anodizing

Define Primary Goal

This is the most critical step. Your main requirement will point you toward the optimal process.

If the priority is exceptional wear resistance and durability for parts facing high friction, pressure, or abrasion, then Type III (Hardcoat Anodizing) is the better choice. It builds a thick, rock-hard layer that significantly extends the service life of components.

If the priority is a high-quality finish with color options and reliable corrosion protection, Type II (Sulfuric Acid Anodizing) is a cost-effective solution, offering the best balance of aesthetics, performance, and value.

If the priority is preserving precise dimensions on critical components, often as a primer for paint or adhesive, then Type I (Chromic Acid Anodizing) is the specialized choice. Its thin, tightly bonded coating protects without altering tolerances.

Specific Part Characteristics

Once you know the goal, practical details will fine-tune your selection.

- Material Compatibility: The aluminum alloy directly affects the result. Alloys like 6063 anodize clearly and are ideal for colored Type II finishes. Alloys with higher copper or silicon content (like 2024) will produce darker, bronze-tone finishes and are better suited for Type III where appearance is secondary to function.

- Part Geometry & Surface: Complex parts with deep recesses or blind holes pose coating challenges for all types, especially thick Type III hardcoat. Additionally, anodizing is transparent—any scratch or machining mark on the base metal will remain visible, so the initial surface finish is crucial.

- Performance Specifications: Define required coating thickness, corrosion resistance (e.g., salt spray hours), and wear resistance. A need for over 0.002″ thickness mandates Type III. For thinner, decorative coatings, Type II is sufficient. Clear specifications ensure the finish meets the functional need.

Consider Production and Compliance Factors

These elements impact feasibility, cost, and lead time.

- Cost Drivers: Type II is generally the most economical. Type III costs more due to longer process times, refrigeration, and precise control. Adding color dyes or specialty seals increases cost for any type.

- Regulatory Environment: The use of hexavalent chromium in Type I is heavily regulated. Many industries now opt for approved alternatives like Boric-Sulfuric Acid Anodizing (BSAA) for similar performance with fewer restrictions.

- Dimensional Impact: Remember that anodic coating grows both into and out of the base metal. For Type III hardcoat, approximately half the thickness adds to the part’s outer dimensions—a critical factor for parts with tight fit, such as threads or bearing surfaces.

The Final Step: Consult Your Finishing Supplier Early

The most effective way to ensure a perfect result is to collaborate with a professional anodizing supplier during the design phase. Provide them with your performance requirements, critical dimensions, and aesthetic samples. Their expertise will help you optimize the design for manufacturability, avoid unexpected costs, and select the ideal type of anodizing for a successful project.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can anodized parts be repaired or reworked if damaged?

The anodic oxide layer is integral to the substrate and cannot be “patched.” To repair a deeply scratched or damaged anodized surface, the existing coating must be completely stripped chemically, and the part must be re-anodized. This process can affect tolerances and the base material.

Is there any alternative to anodizing?

Alternatives include powder coating, electroplating, and various conversion coatings like chromating. Powder coating is a prominent alternative where a dry powder is electrostatically applied and cured into a thick, continuous polymer film.

My parts need both electrical insulation and heat dissipation, which anodizing type is best?

All anodizing types create a non-conductive oxide layer. Type II is commonly used for electronic heat sinks as it provides excellent electrical insulation and adequate thermal conductivity (the heat travels through the underlying metal). Type III’s thicker coating provides even better insulation but can act as a slight thermal barrier if maximum heat transfer is critical.